One of the most incredible journeys I undertook during the writing of All Roads Lead North was to Mustang, to the north of Pokhara. Until a decade ago, one could only walk to Lo Manthang, the capital of the former kingdom of Mustang, or fly to Jomsom (whose airfield was built by Tibetan guerrillas in the 1960s) and walk for a week from thereon.

Today, a dirt track takes 4WD vehicles all the way to the Nepal-China border at Kora La, one of the lowest passes in all of the Himalaya. This dirt track, which was one of the most chilling roads I’ve been on, gives us an idea about how Nepal views infrastructure development as essential to its quest for progress. The proposed Kali Gandaki corridor, connecting Kora La to the plains of Bhairahawa, is one of Nepal’s ‘national pride’ projects that intends to link Nepal with both China and India, wherein Nepal sees itself as benefiting from the growth of its two giant neighbours.

But the national pride project, however, is not in very good shape at the moment. A stretch just before Samar Bhir (cliff) forced me to question my choices: it was either that or live in mortal fear of the nearly half a km straight drop into the valley below.

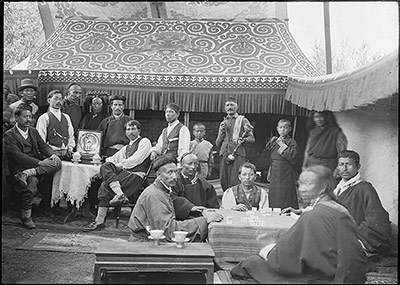

I’ve been fascinated by Lo Manthang for as long as I can remember. It was called ‘a lost Tibetan kingdom’ by French explorer Michel Peissel (whose book on Mustang was my compatriot on this trip), but it was clear that such labels were an exoticised simplification of a people who lived on one of the most prosperous trade routes across the Himalayan region. The Thakalis of lower Mustang were renowned traders; many Thakali homes, however, are empty or crumbling away today, for their families have long moved away from this difficult trans-Himalayan landscape.

Kora La is about 30 kms away from Lo Manthang, if I remember correctly. The road from Chhoser (the last village on the Nepali side) to the border, however, is the widest, and best-maintained, high Himalayan road I’ve been on.

Mustang remains a highly sensitive region for both Nepal and China. It was here that Chinese PLA troops accidentally killed a Nepali soldier in August 1960, where Tibetan guerrillas funded by the CIA set up base and targeted PLA patrols across the border, and where the current Karmapa escaped Tibet on the night of 31 December 1999.

To prevent any more surprises, the Chinese have come up with a simple solution: nearly 20 kms of the border has been fenced with barb wire. It is surreal to see a fence, of all the things, on that height and in that landscape. And yet, it is there.

On our way back, Pasang took me to what must be one of Nepal’s most precious, yet most neglected, archaeological sites: the sky caves.

On my way back, I travelled with an old monk who was going to Kathmandu to arrange citizenship papers and a young man who seemed perfectly at home on this road and liked to drive while playing Nepali rapper Yama Buddha’s songs.

If you’re planning a trip to Lo Manthang, the best time is before or after the monsoons. There are a variety of options – I saw some bikers covered in dust along the way – but the itinerary I hope to do one day is to go to Lo Manthang by jeep, and walk down to Kagbeni. That way, the uphill climbs will not be tormenting!

Jeeps to Lo Manthang are available from Chhusang, two hours beyond Jomsom. Special permits are required to travel beyond Chhusang for non-Nepalis, starting from USD 500 for 10 days.

Further reading on Mustang:

Michel Peissel, Mustang: A Lost Tibetan Kingdom, Futura, London, 1979

Galen Murton, ‘Border Corridors: Mobility, Containment, and Infrastructures of Development between Nepal and China’, PhD Dissertation, Department of Geography, University of Colorado, Boulder, 2017

Carole McGranahan, Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and Memories of a Forgotten War, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2010

Kenneth Conboy and James Morrison, The CIA’s Secret War in Tibet, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, 2002

Tsering Shakya, The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947, Pimlico, London, 1999

Sam Cowan, ‘The Curious Case of the Mustang Incident’, Record Nepal, 17 January 2016. https://www.recordnepal.com/wire/curious-case-mustang- incident/

Manjushree Thapa, Mustang Bhot in Fragments, Himal Books, Kathmandu, 2008

Ramesh Dhungel, The Kingdom of Lo (Mustang): A Historical Study, Tashi Gaphel Foundation, Kathmandu, 2002