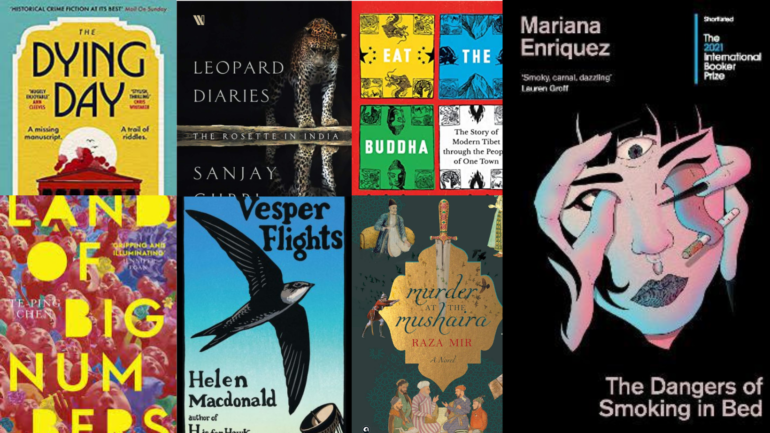

NONFICTION

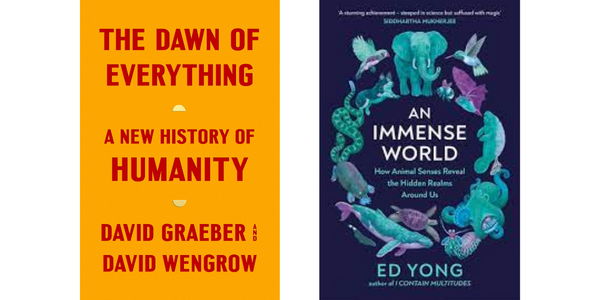

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow

In The Dawn of Everything, Graeber and Wengrow challenge our presumptions about the evolution of human civilization as a linear development from primitive societies to stratified layers as it is today. Instead, the two argue – both with solid archaeological evidence and excellent historical reasoning – that contemporary ideas about humanity emerged from European contact with Native American settlers, and that humanity’s progress towards settlements did not create society’s stratas. The two break down the idea of cultural schismogenesis, or how societies imagine their identities by rejecting what they see being practised around them (one could argue the Upanishadic concept of ‘Neti, Neti’ is similar).

A truly revolutionary book, the ideas in it are radical in how they approach history. As the authors conclude, a different perspective on our history could have meant ‘we could have been living under radically different conceptions of what human society is actually about. It means that mass enslavement, genocide, prison camps, even patriarchy or regimes of wage labour never had to happen.’ Imagine a world like that!

Finally, Graeber’s death in 2020, just before the book was published, makes this book’s radical ideas even more poignant. A rare book that forces you to challenge all your notions.

An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us by Ed Yong

My favourite read of the year. Science journalist Ed Yong takes us on a multi-species journey about how animals perceive the world with a multitude of senses, and what it would mean for humans to imagine the world from their umwelt. We know how well dogs smell, but did you know they are constantly perceiving the world around them through their nose? Does an eye necessarily have to ‘see’ things to be useful for its owner? And what about the sounds that go beyond the human capacity for listening – for examples, when whales communicate across oceans? How do animals use such sounds, and how have they evolved to hear such frequencies?

An Immense World is a book filled with magic and wonder, with every page asking you to step back and imagine the world from a different realm of senses. How would it feel to smell the world go by? Or how would it feel if your eyes were closed and the clickety-clack of a keyboard typing away told you what letters are being typed? This is how animals sense the world – and this is also how humans have changed the world for them, by not considering their senses could be different than ours. As Yong concludes, ‘To perceive the world through other senses is to find splendor in familiarity, and the sacred in the mundane… Wilderness is not distant. We are continually immersed in it. It is there for us to imagine, to savor, and to protect.’

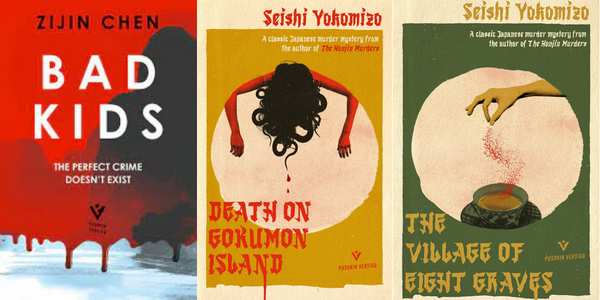

CRIME FICTION

Bad Kids by Zijin Chen was the stand-out crime fiction this year. This translation of a Chinese bestselling novel is premised on a simple notion: three children see a man murdering his in-laws, and now they want to make some money. Therein lies a tale about deceit, the loss of innocence, and a world where children are forced to turn adults as the violence begins to spiral.

Cult Japanese crime writer Seishi Yokomizo’s two books – The Village of Eight Graves and Death on Gokumon Island – were both published this year. Both are in the inimitable Seishi style that take us into the heart of Japan’s post-WWII dilemmas, and translated brilliantly. Pushkin Vertigo, which published Bad Kids and all of Seishi’s translations as well as other Asian crime fiction, is turning out to be my favourite publisher.

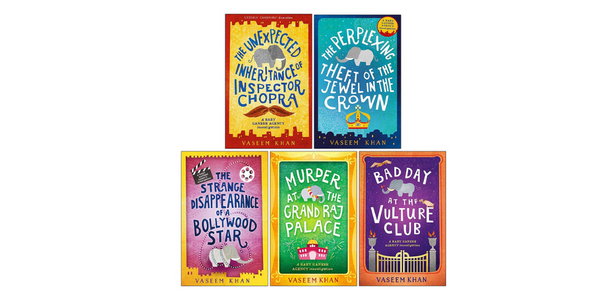

British-Indian writer Vaseem Khan has recently started an excellent new series with India’s first woman police detective, the Parsi Persis Wadia, as protagonist. This year, however, I read the five Baby Ganesh novels – about retired inspector Ashwin Chopra and a baby pachyderm sidekick, named Ganesh. The easy-reads take us into the heart of Bombay, pulsating with its glamour and its stars – and the suspension of disbelief that is required not just to keep a baby elephant as a pet in today’s Bombay, but also the ease with which Chopra beats the city’s traffic. A great holiday read!

LITERARY FICTION

Funeral Nights by Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih

Rare is the novel that can claim to tell the story of a people in its entirety. Funeral Nights perhaps comes closest to this claim, taking its readers deep into the heart of Khasi history, folklore, society and worldview. A group of friends decide to travel to witness the Ka Phor Sorat, a six-day-long traditional funeral ceremony at the end of which the elder woman, whose body has been preserved for nine whole months in a treehouse, is cremated. All along the way and in the village, the friends turn raconteurs, telling each other stories and anecdotes about their worlds. A magnificent novel that deserves the label ‘tour-de-force’.

The Devourers by Indra Das

What would you do if you met a werewolf in modern-day Calcutta, especially a werewolf who tells you he’s seen the death of the Mughals and the birth of the British Empire? Indra’s prose is immaculate as he takes his readers on a fantastical path through history, all the while reminding us what it means to be human and to love. The Devourers is one of South Asia’s standout fantasy works, and although I came to it late, it deserves to be widely read, if only to understand what makes one human, and a monster.

We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies by Tsering Yangzom Lama

Among this year’s books, I felt closest to Tsering’s debut novel, which has received rave reviews across the world. Shifting across geographies and time, this is a book about exile, the loss of home, and of Tibetan families scattered across the world. But this is equally a story about what it means to be a Tibetan exile, and how, as the protagonist says at one point, ‘People find our culture beautiful…But not our suffering.’ An extraordinary and moving debut that brought not just Tibetan exiles but also new Tibetan writing into the global mainstream, We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies is a rare novel that will resonate with anyone who seeks out the Himalaya.

The Committed by Viet Thanh Nguyen

While The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s acclaimed debut, was globally acclaimed, I found the sequel, The Committed, to be a much more polished novel. It begins with the unnamed protagonist of The Sympathizer arriving in Paris with blood-brother Bon with a bloodlust for all Communists. In Paris, the narrative turns on its head, becoming an evocative crime saga that goes into the heart of the choices immigrants have to make in new worlds. A fantastic read.

The Birth Lottery and Other Stories by Shehan Karunatilaka

First, an appetising disclaimer: Shehan’s new story collection is represented by Writer’s Side Literary Agency, where I am consulting editor. (We had a great year at the Agency. Both the International Booker Prize and the Booker Prize were won by our authors – Daisy Rockwell for her translation of Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand and Shehan’s Seven Moons of Maali Almeida respectively.)

Now, the main course: Although the Booker prize has thrust him into the international spotlight, Shehan has long been one of South Asia’s most perceptive – and imaginative – writers. Few novels can match the scope, wit and dark humour of Chinaman, but if I were to compare, I’d say the stories in The Birth Lottery show off his entire oeuvre. This is a wild, wild story collection, one of the best I have read (and had the pleasure to work on) in recent years, and in all likelihood, an instant classic. I won’t sell it more, but do yourself a favour and pick this up if you’re into LTTE time travellers, breakaway island-nations, the goals of reincarnation, and adultery in a time of civil war.

BOOKS ON THE HIMALAYA

Shadow States: India, China and the Himalayas, 1910-1962 by Berenice Guyot Richard

In Shadow States, political scientist Berenice Guyot Richard describes the nature of statemaking in the eastern Himalaya, where British and independent India, Tibet under the 13th Dalai Lama, and China – both revolutionary and Communist-ruled – strove for control of a land dominated by local ethnicities with their own sovereignties. An excellent monograph on how these powers tried to bring this region under their control, and a timely reminder when the India-China border dispute has once again dominated the discourse.

The Mandala Kingdom: A Political History of Sikkim by Alex McKay

A fantastic introduction to the contentious history of Sikkim until 1948. McKay’s history of the once-Himalayan kingdom is accessible, and cuts across several myths to provide a clear structure of how Sikkim shifted its allegiances from Lhasa to Calcutta. The now-Indian state’s past describes how pre-colonial political structures manifested themselves in the Himalaya, and how colonial ambition marked the end of the Mandala tradition of political rule. (Also, the publisher is Rachna Books of Gangtok, whose publishing list is turning out to be a dream for a Himalayan citizen.)

The Nanda Devi Affair by Bill Aitken

Bill Aitken’s classic memoir of his travels around the Nanda Devi valley is also a story about why humans have been fascinated with the mountains. While colonial expeditions under Shipton opened up the valley to outsiders, it is the lore around Nanda Devi that turns this into a most-readable text.

Vignettes of Nepal by Harka Gurung

In similar vein as Aitken’s memoir, except this one by the legendary Nepali geographer Harka Gurung, who passed away in a tragic 2006 helicopter crash that took with it several intellectuals of Himalayan studies, is about his own travels across Nepal in the 1960s and 70s. Vignettes appeals both to the romantic who believes in an untouched Himalaya, as well as someone like me who likes to compare the evolution of the region since Gurung’s time.

Vanishing Tracks: Four Years Among the Snow Leopards of Nepal by Darla Hillard

Hillard’s memoir recounts the first-ever scientific expedition to radio-collar snow leopards in the Mugu region of Nepal in the 1980s. While it should be read as an account of a pioneering scientific expedition, there are also elements within it that point towards Hillard’s own stereotypes and generalised statements about the locals she works with and meets. Nonetheless, this is an important text to get a sense of local indigenous beliefs about their wildlife, and how science must assist in local knowledge and conservation initiatives.

Buddhist Himalaya: Travels and Studies in Quest of the Origins and Nature of Tibetan Religion by David Snellgrove

Snellgrove’s classic text, written in the 1950s when he first arrived as a young scholar, is a fascinating explainer on the nuances of Tibetan Buddhism, especially for a non-practitioner like me. How did Tibetan Buddhism evolve from early Buddhist precepts to a multi-layered world of demons and deities? What is the significance of the five Buddhas? How are stupas and monasteries designed? This text fills in these blanks to give us a rounded picture on the evolution of the religion.

MOST DISAPPOINTING BOOK OF THE YEAR

I usually don’t write about books I didn’t like, but for the first time, I have singled out British historian John Keay’s Himalaya: Exploring the Roof of the World as a text that disappointed me in its entirety, except for its recollection of new geological and archaeological research on the Himalaya.

Keay’s book is a story not of the Himalaya, but of imperial encounters with the Himalaya and its people. It should have ideally been subtitled ‘Colonizing the Roof of the World’.

Let me be blunt: Himalayan histories need to stop being imagined as the story of imperial officers putting their lives and minds at risk in service of queen and country, or the story of esoteric religious practices that defy Western worldviews and thus provide fertile ground for mysticism. The Himalaya is not an exotic unexplored region built up through Western fantasies of masculinity and imperial grandeur. It was, has always been, and will always be a place where several cultures have converged, and the colonials were but another piece in a long history of peoples who have been fascinated by the mountains.

I could be blunter, but let me leave you with Keay’s atrociously self-centred conclusion about the fragile state of the Himalaya in the modern era of climate change: ‘[T]he concerns of the indigenous peoples should not be allowed to deter global anxieties.’ This should tell you what the book is about.